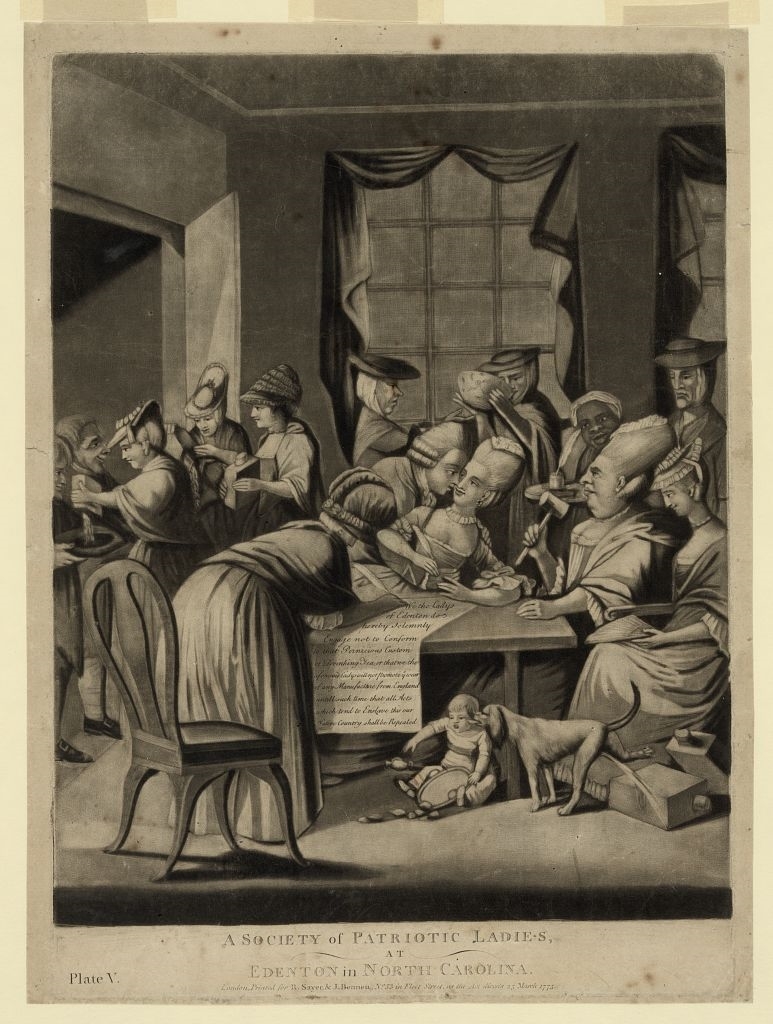

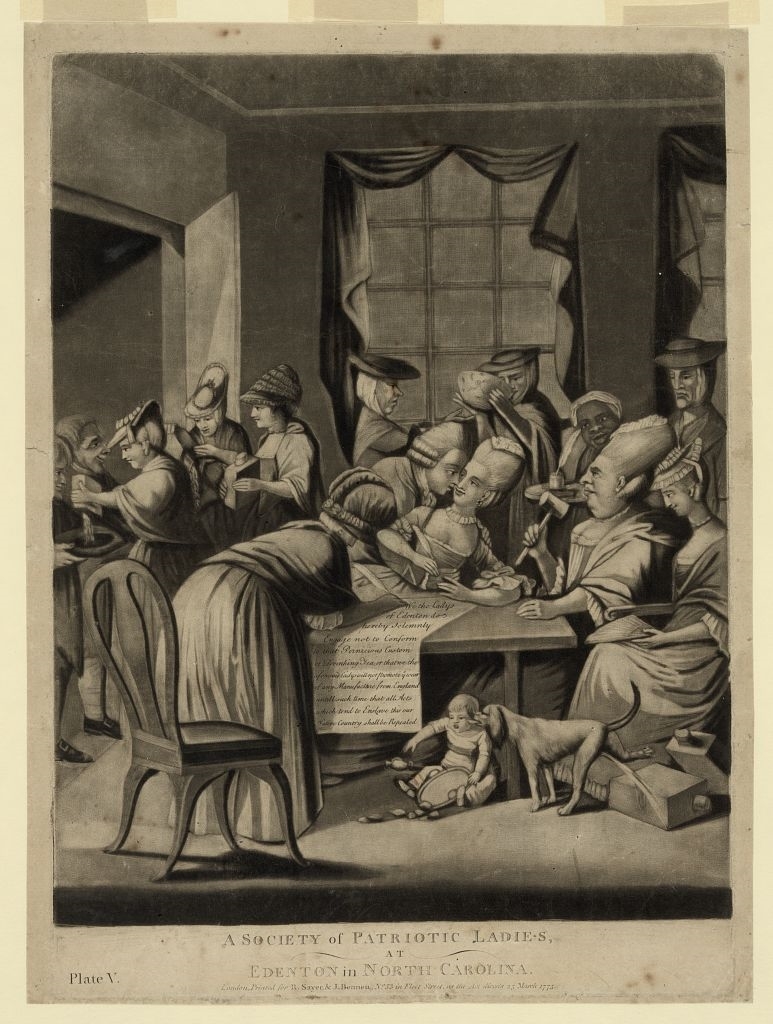

Philip Dawe, “A Society of Patriotic Ladies, at Edenton in North Carolina,” 1775, mezzotint, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

In the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, caricatures--like the one above--lampooned political women. The mezzotint depicts the women of Edenton, North Carolina who gathered to boycott British tea in 1774. They gather to sign the boycott, while a particularly masculine-looking woman on the right watches over the proceedings. The group ignores the child under the table, which suggests that when women participate in politics they ignore their domestic duties. They lose their physical beauty as well.

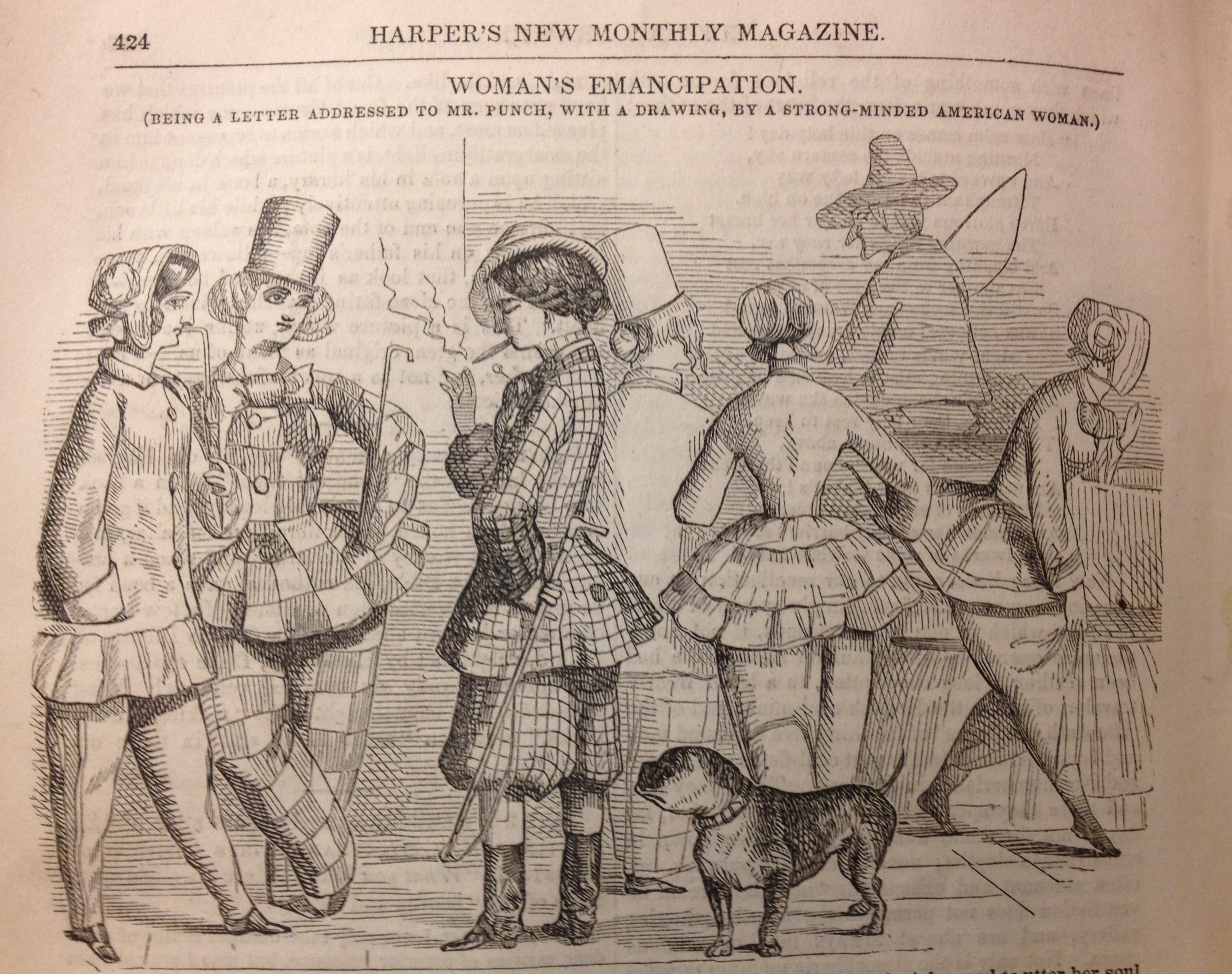

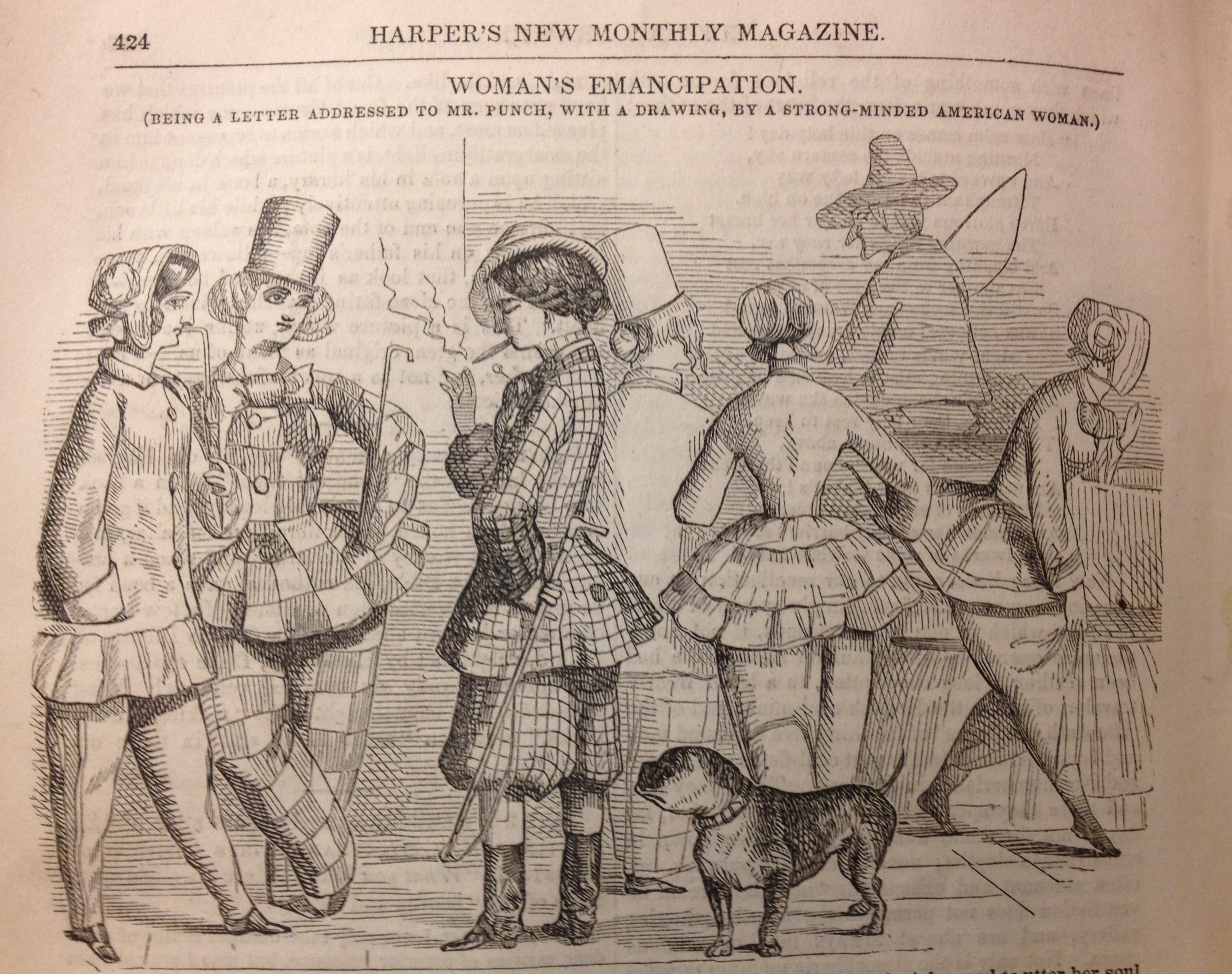

“Woman’s Emancipation,” 1851, engraving, published in Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, August 1851, 424, Boston Athenaeum.

When woman organized in the 1840s, they demanded better education, employment, and control over their money and property. Artists, however, continued to caricature political women in a similar manner, ensuring that no one took them seriously.

This 1851 engraving depicts six women wearing top hats and the scandalous bloomer costume instead of traditional dresses while smoking on a street corner. These masculine women drive away the sole man in the scene. While cartoonists did not officially band together to condemn woman’s rights, the great quantities of pictures like this one ensured the dominance of this message. The cartoons policed gender roles and undercut the efforts of reformers.

J. Rogers and John Wollaston, Mrs. George Washington (Martha Dandridge), 1855, engraving, published in Rufus Griswold's The Republican Court, New York Public Library Digital Collections.

Female activists were caricatured, but First Lady Martha Washington became an icon of idealized political womanhood. For example, this portrait from an 1855 book depicts Washington as a beautiful young woman in a garden. The author lauded her beauty and hostess skills because she never forgot “the requirements of feminine propriety.” Indirect political participation, especially to support one’s husband and family, was a prized form of female patriotism. (For more on my work on Martha Washington, click here.)

Sojourner Truth, 1864, photograph carte de visite, Harvard Art Museum/Fogg Museum, Fine Arts Library, Harvard College Library.

Former slave Sojourner Truth was among the first female activists to carefully shape her public image. Unlike other famous people who allowed photographers to sell their portraits, she sold them herself.

While Truth’s portraits vary slightly, they consistently show her adopting the visual conventions for representing respectable white middle-class matrons. In this portrait, Truth sits next to a table with her knitting needles and looks up as if the photographer interrupted her mid-stitch. She wears wire-rimmed glasses that refer to her intelligence and inclusion in elite, educated circles. Truth had to claim respectability in her portraits in a way that white female reformers did not.

“Portraits of Stanton and Anthony Together,” ca. 1870-1895, carte de visite, Schlesinger Library on the History of Women in America.

After activists created the first national suffrage organizations in 1869, they decided to take control of their movement’s public image as well. Leaders, especially Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony, used portraits like this one to establish themselves as prominent leaders. Together the women look formidable. Stanton’s stare (or glare?) directly at the viewer is the most striking detail. Both women wear traditional, fashionable dresses, rather than the bloomers they had worn fifteen years earlier.

Left: J. C. Buttre, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, 1881, engraving. Right: G. E. Perine & Co., Susan B. Anthony, 1881, engraving. Portraits published in History of Woman Suffrage, volume one.

These portraits of Stanton and Anthony appeared in the first volume of the History of Woman Suffrage (1881) and resembled popular imagery of male politicians. Unlike portraits of Martha Washington, these pictures don't emphasize their beauty or depict them as mothers. Instead, they represent them as serious figures contemplating the future.

The History of Woman Suffrage series was the first major effort to establish a historical narrative of the movement well as a tableau of its leaders. The editors took advantage of the gentility implied by their white skin and featured portraits of only white women. Later in the 1890s, black reformers began publishing books with portraits of black suffragists that aimed to claim the prominence that they were denied.

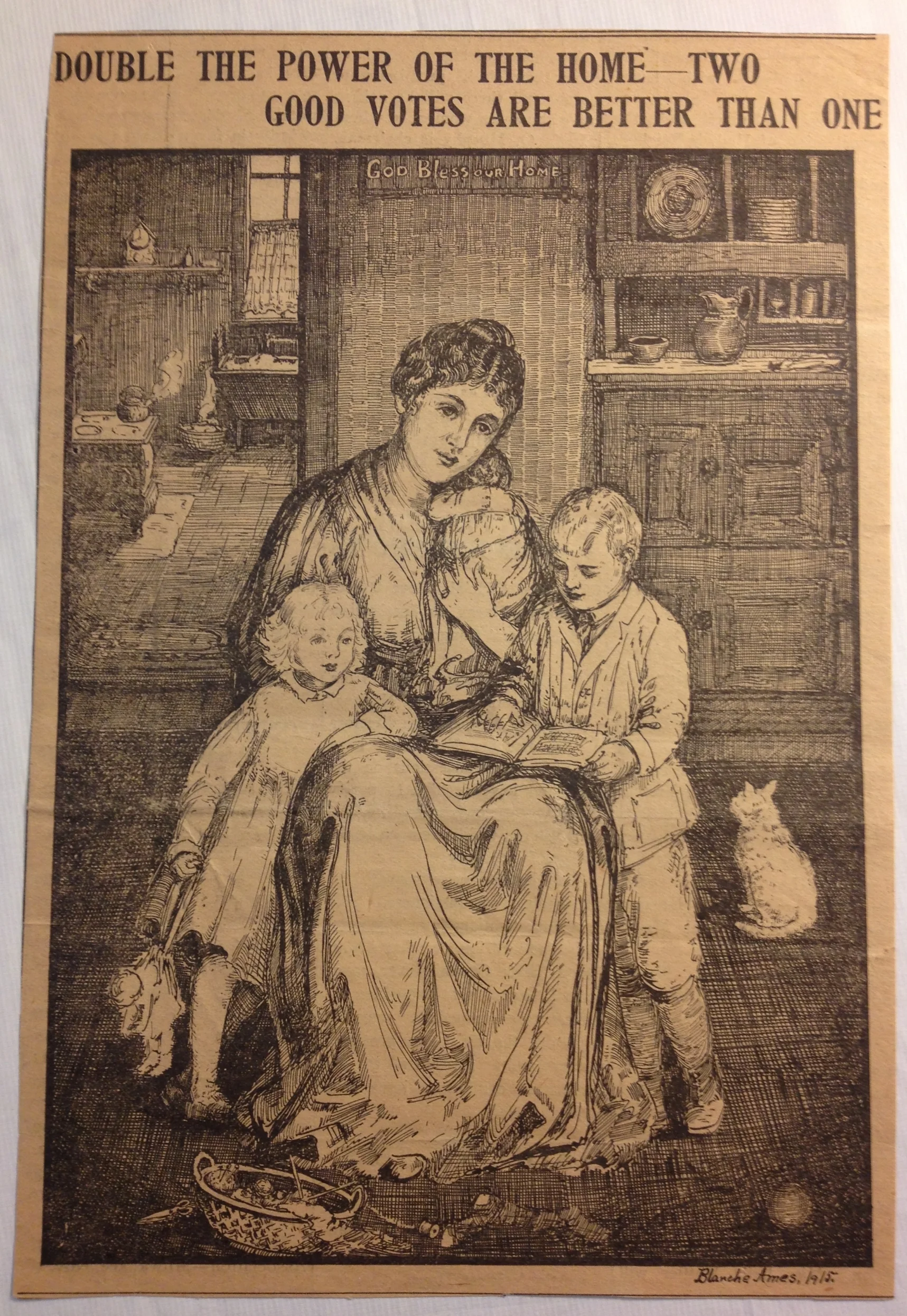

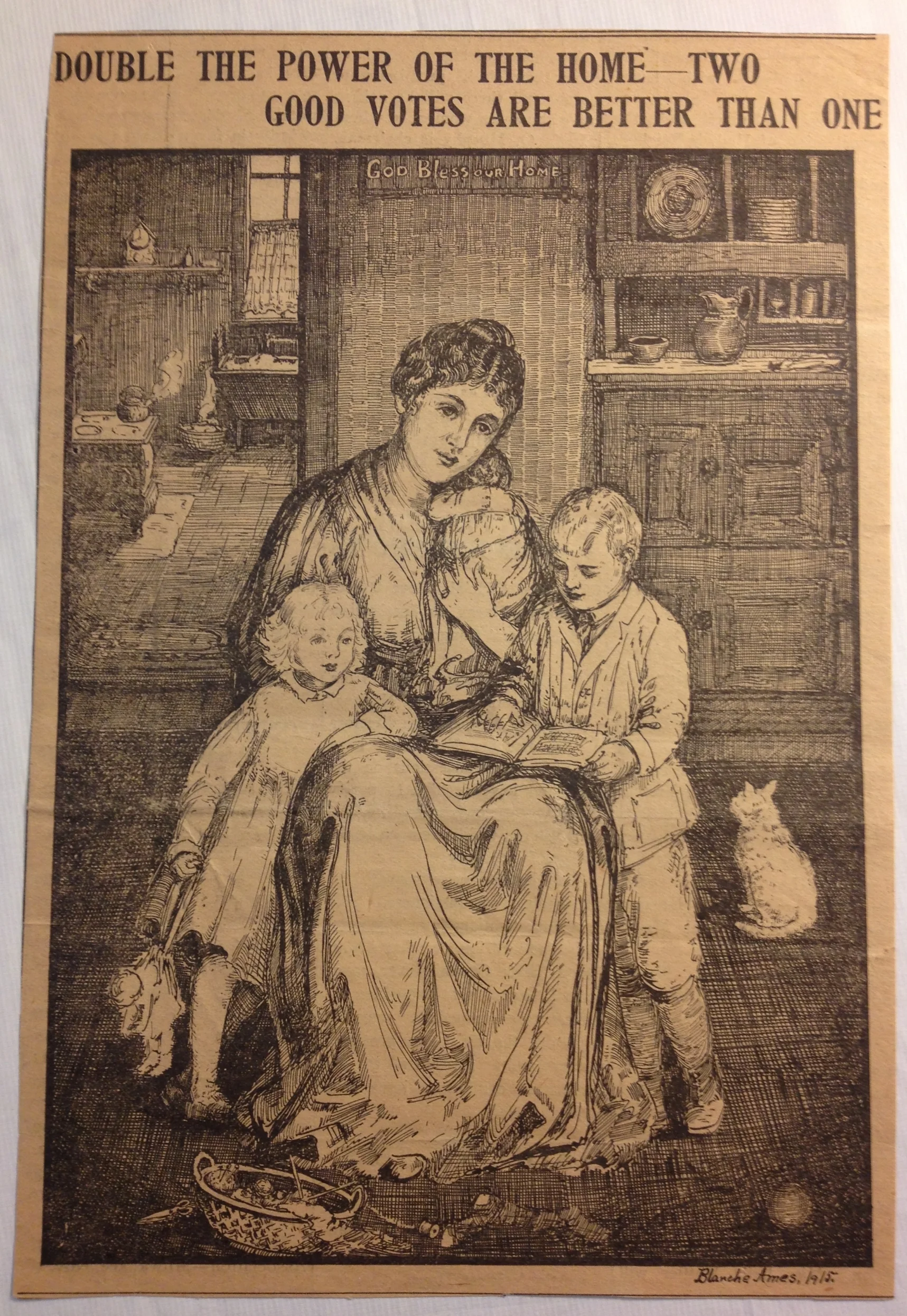

Blanche Ames, “Double the Power of the Home—Two Good Votes Are Better Than One,” 1915, engraving, published in The Woman’s Journal, October 23, 1915 and the Boston Transcript, September 1915.

In 1890, suffragists merged into one national organization: the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA). Instead of relying on the efforts of individual leaders, NAWSA decided to establish new committees in charge of press and art publicity.

Their imagery changed too. NAWSA emphasized that suffragists were good mothers who wanted to apply their expertise to improve society. This 1915 engraving by suffragist Blanche Ames depicts a young woman with an angelic face with three children surrounding her. An idyllic home, complete with a “God Bless Our Home” sign, provides the backdrop. Ames argues that a good white privileged mother like this one would positively influence politics.

“Mrs. Mary Church Terrell,” 1900, engraving, The Colored American, February 17, 1900.

Since NAWSA excluded black women and ignored their concerns, black women had to construct their own movement. Established in 1896, the National Association of Colored Women (NACW) focused on the broader goals of racial and gender equality. Still, political imagery of both groups emphasized the respectability of suffragists. Between NAWSA and the NACW, visual propaganda that promoted suffragists as virtuous wives and mothers dominated the movement’s imagery through 1920.

![Harris and Ewing, "Penn[sylvania] on the picket line-- 1917," 1917, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Collection.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55809242e4b051888f79d0c3/1436281329188-695UQMJKH06FESMZ5UY8/Picket+jpeg.jpg)

Harris and Ewing, "Penn[sylvania] on the picket line-- 1917," 1917, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Collection.

The imagery of the National Woman’s Party (NWP), founded in 1913, rejected the emphasis on feminine virtue. In the 1890s, the adoption of the halftone printing process allowed for the cheap reproduction of photographs in newspapers for the first time. The NWP took advantage of this new technology. They coordinated spectacular protests that ranged from parades to pickets in order to attract news photographers.

When the United States entered World War I in 1917, NAWSA circulated visual propaganda and news photographs that emphasized women’s patriotic contributions to the war effort. That same year, press photographers snapped pictures of the NWP picketing the White House. The controversy over the NWP’s news photographs of suffragists picketing, imprisoned, and going on hunger strikes forced politicians to address the issue. Even so, male political leaders embraced dominant rhetoric of respectable, patriotic political womanhood to justify their support for the Nineteenth Amendment. Women won the vote when they created a visual campaign that countered over a century of opponents’ cartoons, incorporated new visual technologies, and developed professional campaign strategies.

![Harris and Ewing, "Penn[sylvania] on the picket line-- 1917," 1917, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Collection.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55809242e4b051888f79d0c3/1436281329188-695UQMJKH06FESMZ5UY8/Picket+jpeg.jpg)