Photo by Kelly Benvenuto Photography

Exhibitions

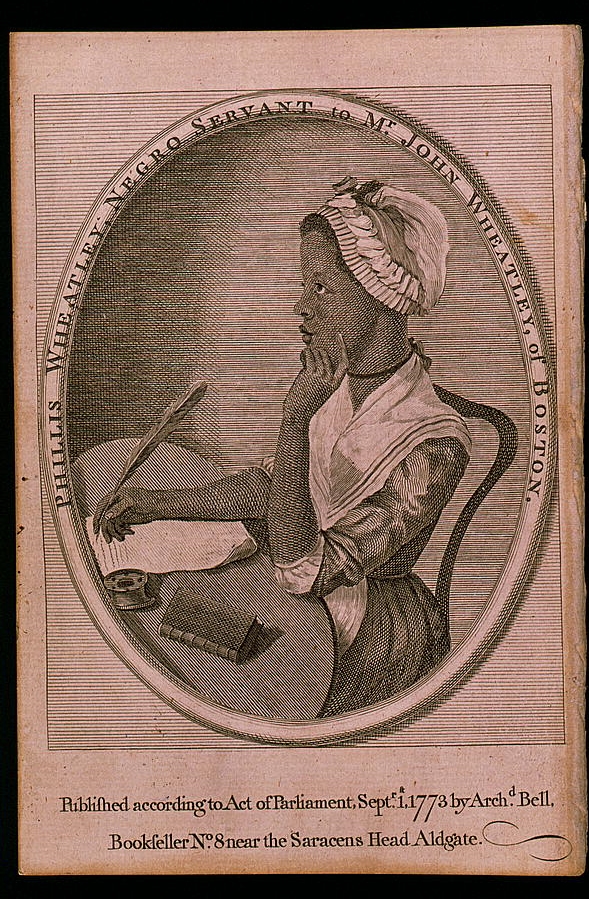

Curator, Truth Be Told: Stories of Black Women’s Fight for the Vote Digital exhibition here, Summer 2020

Melinda Gates’ organizations Pivotal Ventures and Evoke

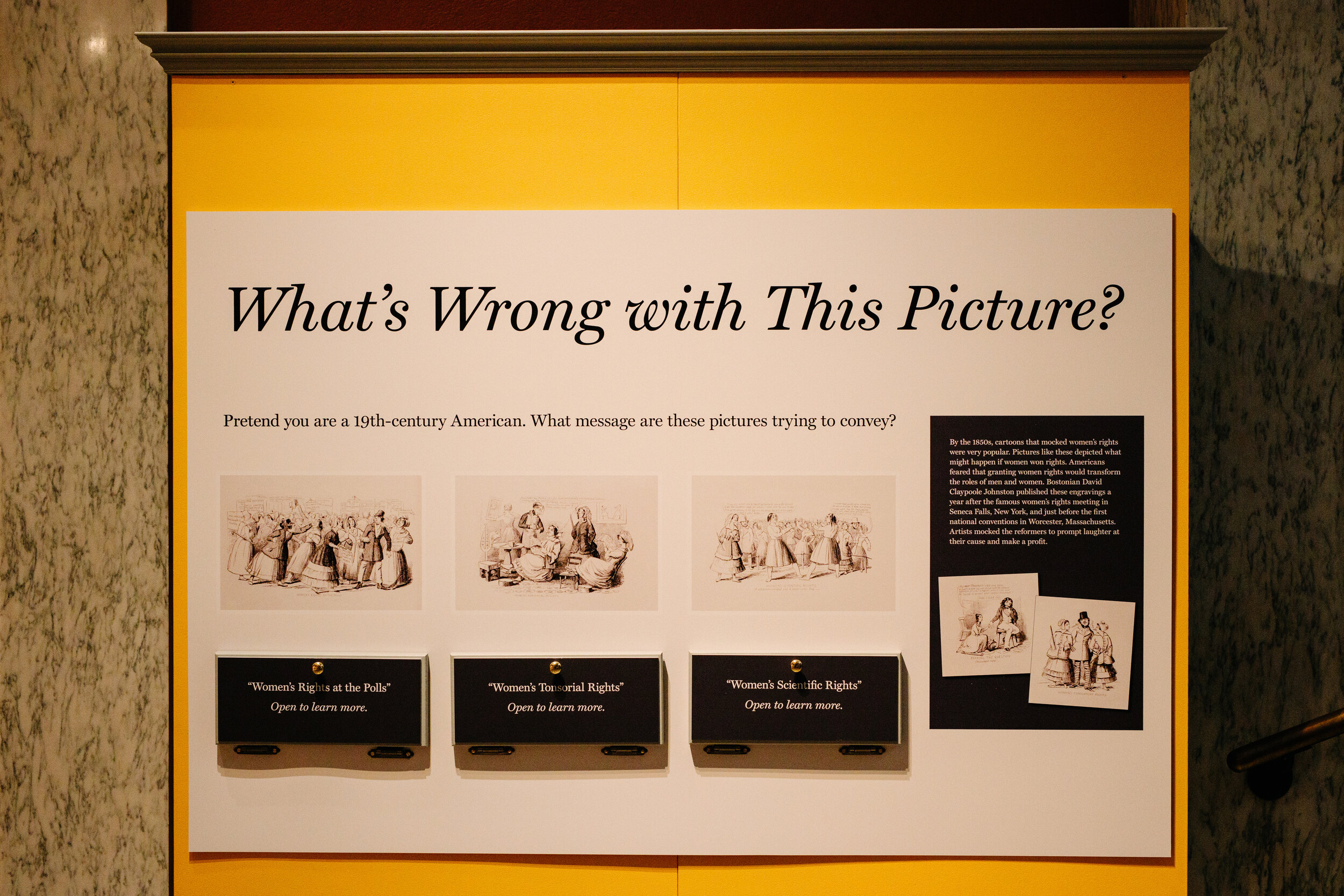

Curator, Seeing Citizens: Picturing American Women’s Fight for the Vote

Digital exhibition here, Summer 2020

Harvard University’s Schlesinger Library on the History of Women in America

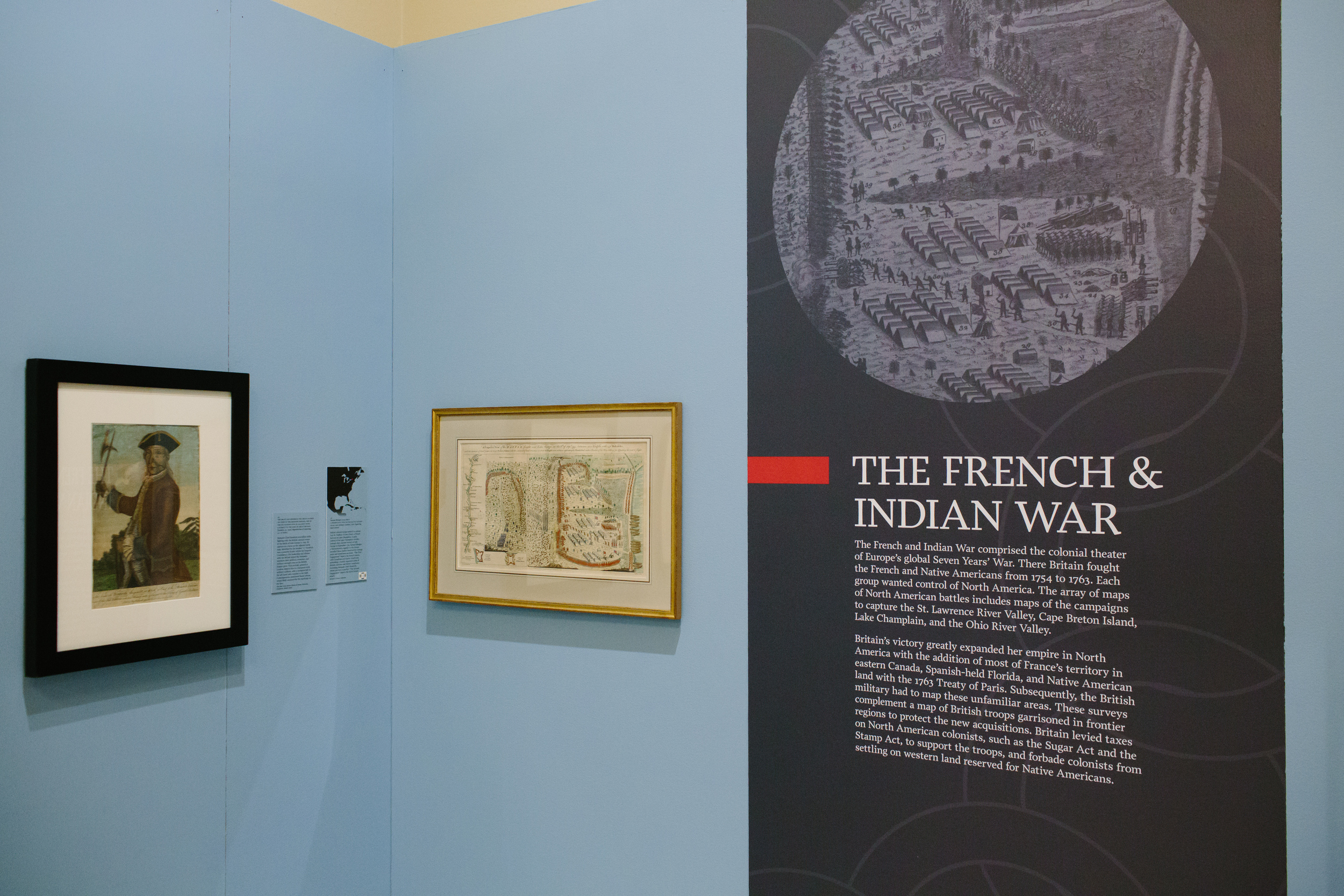

Assistant Curator, America Transformed: Mapping the Nineteenth Century

Part one open from May through November 2019, part two open from November 2019 through May 2020, digital exhibition here

Norman B. Leventhal Map Center, Boston Public Library

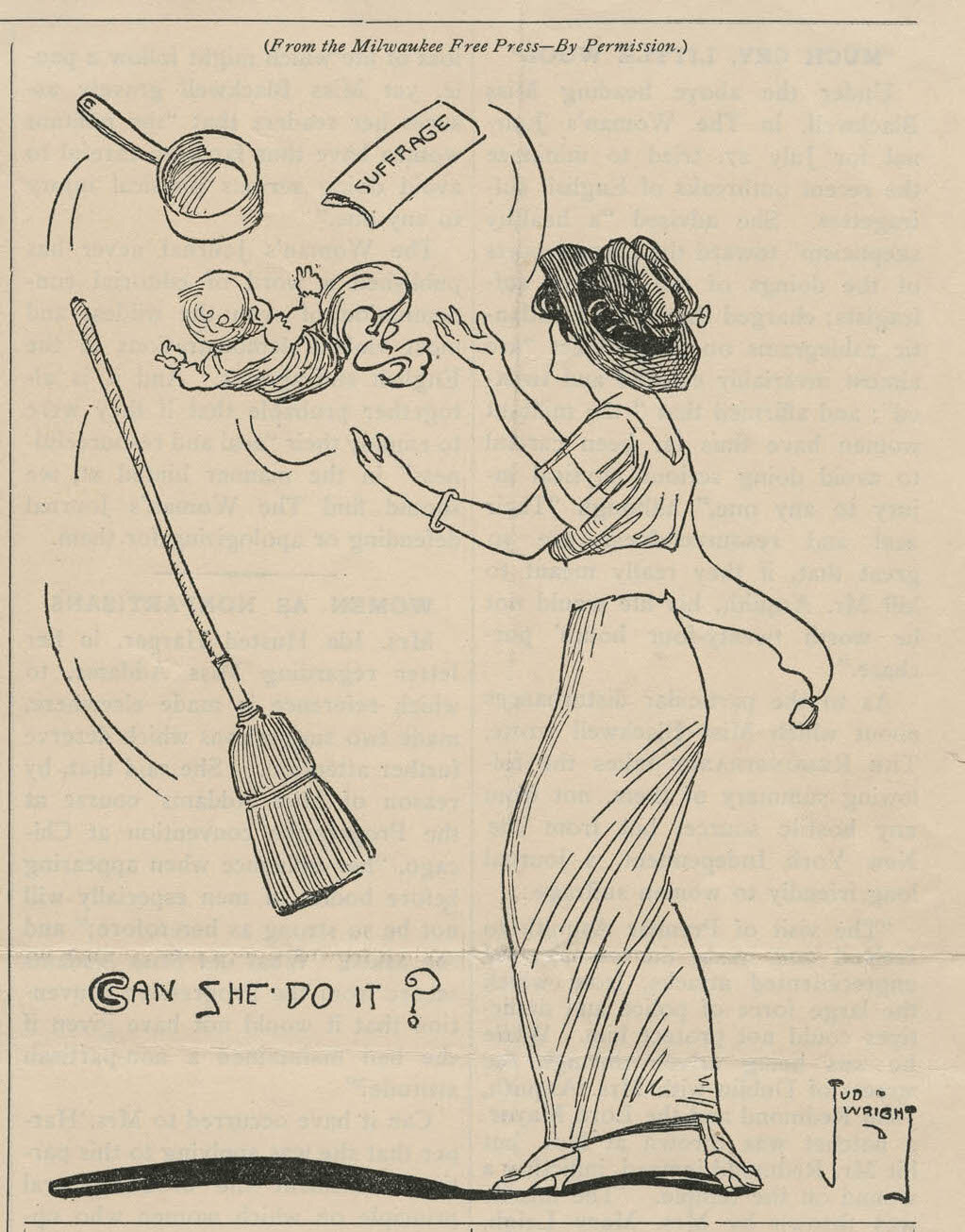

Curator, Can She Do It? Massachusetts Debates a Woman’s Right to Vote On display from April through September 2019, digital exhibition here

Massachusetts Historical Society

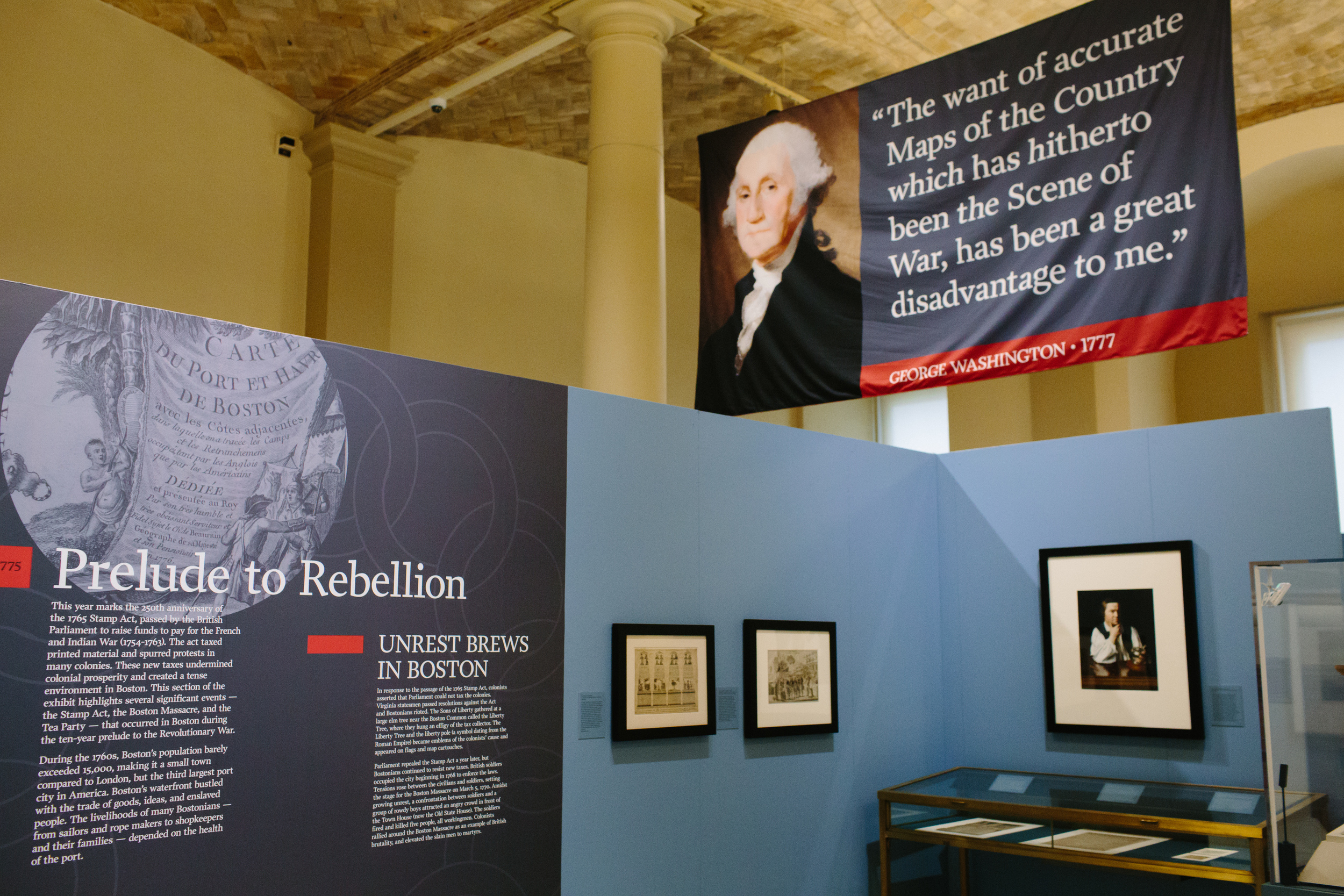

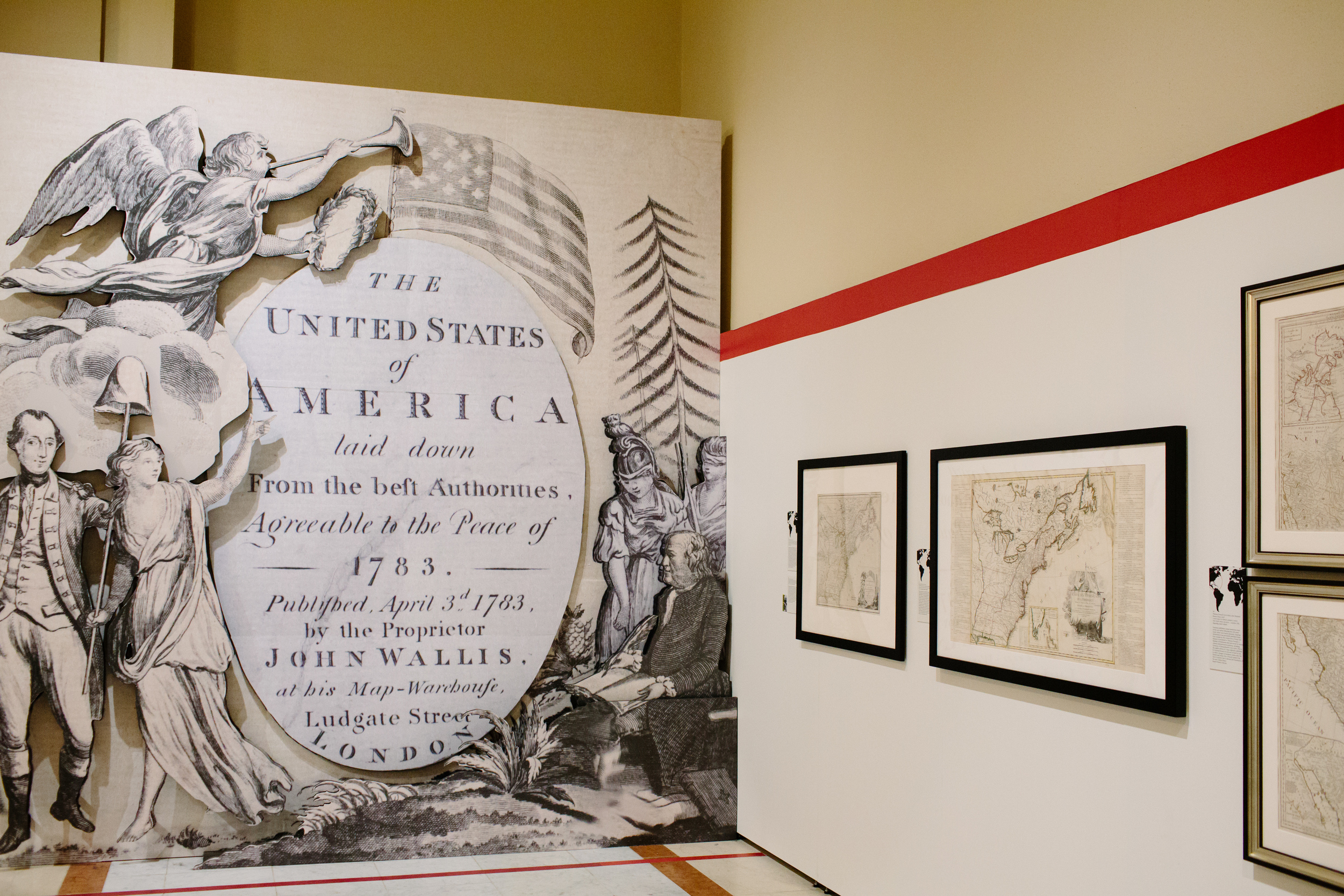

Exhibition Research and Curatorial Assistant, We Are One: Mapping America’s Road from Revolution to Independence

On display in 2015, exhibition traveled to Colonial Williamsburg and the New-York Historical Society in 2016 and 2017, digital exhibition here

Norman B. Leventhal Map Center, Boston Public Library